Rules!

There were always rules. Don’t talk with your mouth full. Don’t eat in the street. Make your bed. Don’t pick your nose. (I still do, though.) Chew your food 32 times before swallowing: this one perhaps did not last. Say please. Say thank you. Wipe your feet. Wash your paws. Brush your teeth. Don’t interrupt. Say “Please may I leave the table.” Some of these were puzzling and I would ask “why?” and then “why?” again, and perhaps then “but…” whereupon my mother would bring out the unfairest rule of all, “don’t contradict.” That was definitely a sign she was cross.

Her anger could be terrifying and remained so. As a teenager I was stomping upstairs after some argument and she said in her fiercest voice, “Come here.” Against my will, my feet stopped. I couldn’t go on. I reluctantly dragged myself back down. My brother told me that, thirty years old, he still automatically stubbed his cigarette out when she walked into the room.

My parents started to argue. I got stomach aches. I told Mum and she would hold me curled up against her. There it was comforting and safe.

But she would talk to herself, a quick, quiet, constant patter, looking at herself in the bathroom mirror. Once I asked her why she was doing it and she said, to my surprise, “I suppose it’s what people do when they are lonely.” I didn’t understand this, though I knew what the word meant.

Once, in the Stone House, their argument was really bad, and Dad went upstairs and wouldn’t come back down. I climbed up the stairs, which were wooden with gaps between each step, and told him “Mummy says she’s sorry”. I knew this was not true, but I was surprised that he did not seem to believe me and did not respond.

My father talked about these fights when I was an adult. “I became extraordinarily eloquent,” he said, with something like amazement. I doubt that he won many, though. Mum was not as articulate, but she had a huge energy and knew that fights were won by stubbornness not reason.

She could also be very deflatingly funny. “Hoity toity!” she would say. That came from grandmother and Derbyshire. A down to earth culture. Mum didn’t talk much about her family; she had been the first to go to university, winning a scholarship to Oxford in the 1950s. But there was a souvenir teapot from there in the Stone House, which said round the side DAUN EE WASTE THE TAY. And as well as stories of her school, she told me about the shepherd’s counting scheme: ethera, tethera, dick, tick….

I remember one very happy summer at the cottage. This was when Mum went to India. Dad and me played all summer in the river, by the bridge in the village, making engineering works in shingle beds. That was 1983, and the summer was hot and long. (A year or two ago the farmer tore out the copse by the river, which was a Site of Special Scientific Interest. I am pleased to say they jailed him.)

In India, Mum was visiting old friends. She and Dad had been out there in the 1960s for two years, and my middle brother had been born there. He had worked on a newspaper. They had known poets and artists in Bombay. Her best friend was a Gujarati lady who she’d kept in touch with by letter for 20 years. They had visited the Valley of Flowers together in Kashmir, before it had become touristy, and before the civil war had started. She corresponded with all of her Indian friends, sent them poems and got copies of their verse back. Some of them became famous.

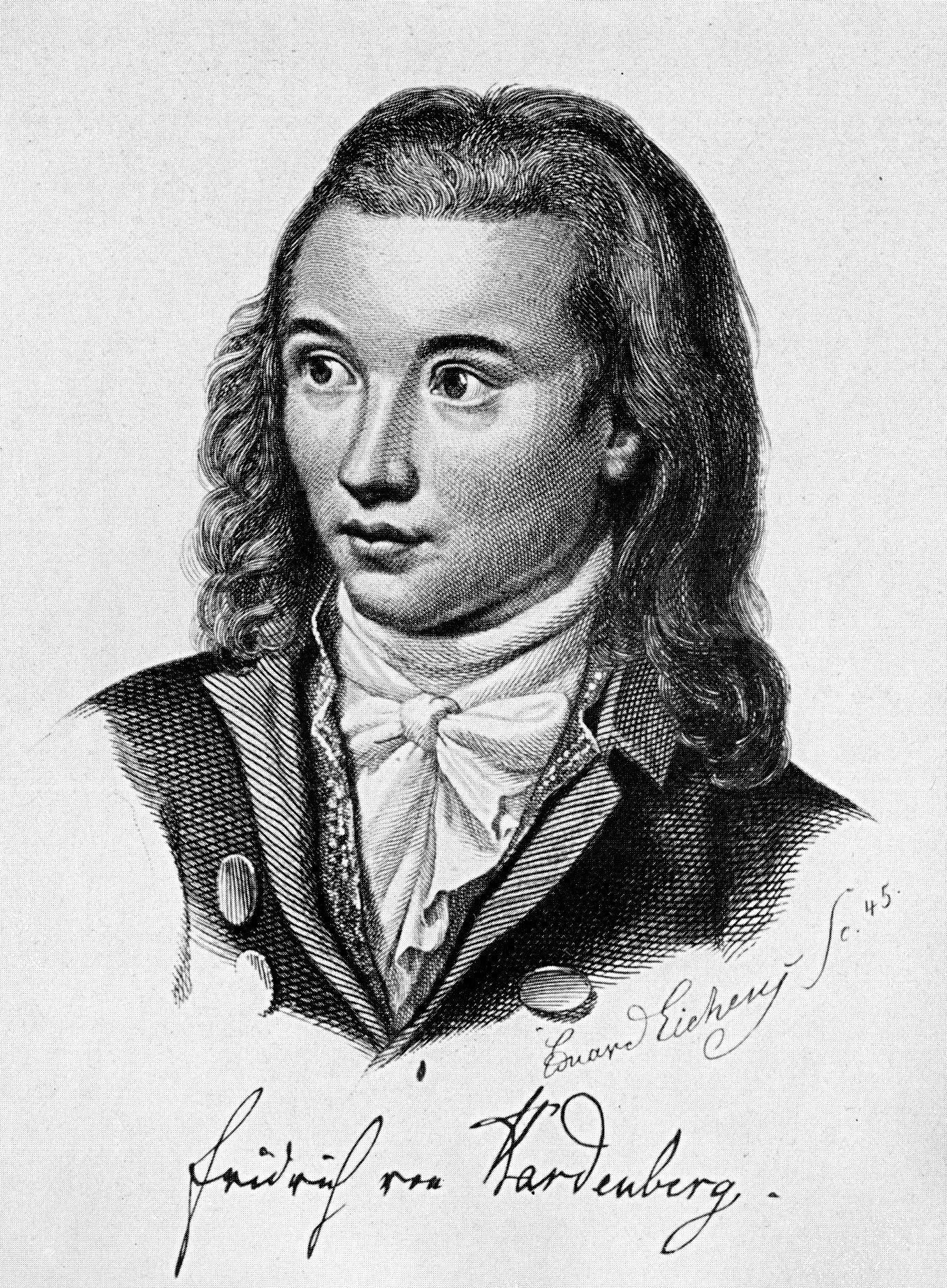

She never bothered with publishing much, though I am not sure if she had tried earlier. She wrote poetry, a lot, some of it good. She could write comic verse or serious work, she could write in French or translate from French or German, which she’d studied at Oxford. (“Don’t say studied. Say read.”) Here’s her reading of Novalis:

When numbers, figures, names and lists Won’t be the key to what exists When I who sing and you who kiss Have outlived sociologists...

Once we wrote a children’s book together about our dogs. One of the dogs was kidnapped by Mr Jackson, a wicked Jack Russell terrier owned by a friend of ours. Mum did illustrations and I came up with the words. We sent it to publishers, who wrote back kindly. Sometimes she would write out nonsense verse from Edward Lear and illustrate it.

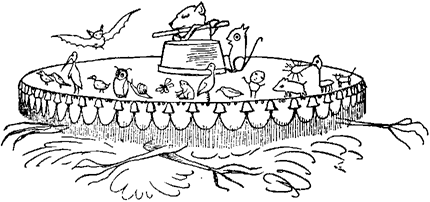

She sent one of these to my middle brother in California. It was the Quangle Wangle’s hat, with a picture of all the creatures under the hat: the Pobble who has no toes, and the Small Olympian Bear. I saw it when I was staying with him and told him how sad it seemed to me. He told me that was a symptom of depression: “there’s no way that’s a sad poem.” But I couldn’t help seeing it so. Life on the whole is far from gay. The hat, which is home to so many varied creatures. But his face you could not see, On account of his beaver hat. Indeed in her drawing the person under the hat is invisible.

In 2014, she put together a selection of her favourite poems and typed a few copies out, bound them up with ribbon, and drew a holly leaf and wrote “Happy Christmas” on the front. She sent them to her best friends, to her children. One was addressed just to “Hugh-Jones” at the address of Dad’s flat in London. I picked it up there and asked Dad if he wanted it, but the subject changed and he forgot to reply.